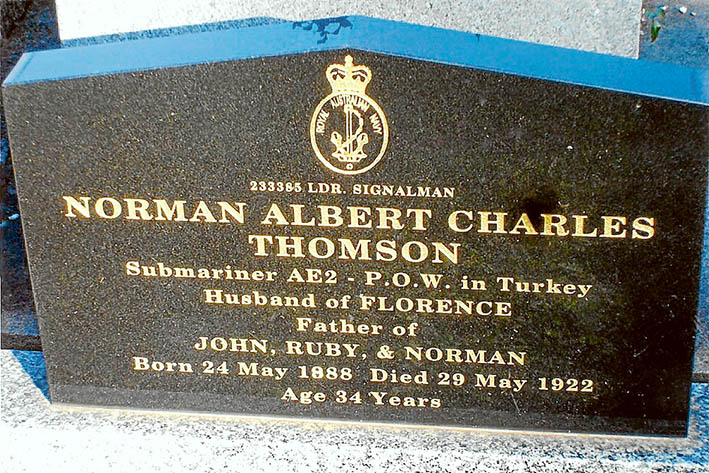

IN a quiet corner of the Tyabb cemetery in Hastings can be found the grave of Leading Signalman Albert Norman Charles Thomson. For decades the grave had no means of identification but about eight years ago a headstone was erected. So much time had elapsed since Thomson’s death in 1922 that an error has occurred and he is identified as “Norman Albert” instead of “Albert Norman.” However the line below the name reflects the role that this sailor played in our history: he was a submariner on the AE2 and, subsequently, a prisoner of war in Turkey.

What was the AE2?

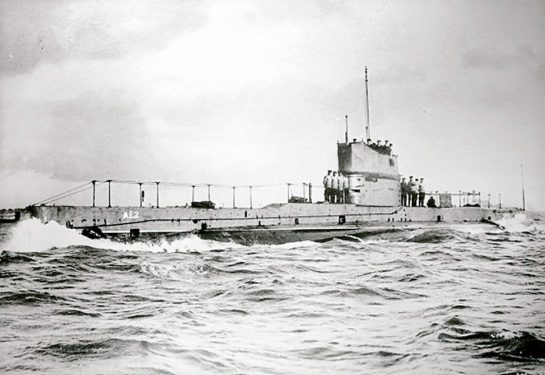

HMAS AE2 was one of two submarines ordered by the fledgling Royal Australian Navy. It was built by Vickers Armstrong at Barrow-in-Furness in England and commissioned into the RAN at Portsmouth in February, 1914.

The AE2 had four 18-inch torpedo tubes, one each in the bow and stern, plus two on the broadside, one firing to port and one to starboard. The boat carried one spare torpedo for each tube. No guns were fitted.

Lieutenant Henry H G D Stoker RN had command of the AE2 and it was manned by Royal Navy officers with a crew drawn from both the RN and RAN.

Together with her sister submarine, the AE1, the boat then sailed to Australia. The 24,000km voyage was at the time the longest one ever undertaken by a submarine and took 83 days.

At the outbreak of World War I both submarines were assigned to the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force as it captured German New Guinea. While on this assignment the AE1 disappeared without trace and its whereabouts are still a mystery. After some weeks patrolling around Fiji the AE2 returned to Sydney in November for maintenance and repairs.

With no need for submarines in the Pacific or Indian theatres, the AE2 was towed to the Mediterranean and arrived off Egypt in early 1915. There the boat was assigned to the Dardanelles campaign, the aim of which was to knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war and open up supply lines to Russia through the Black Sea. Attempts to open the Dardanelles using naval power were unsuccessful with three Allied battleships sunk and another three crippled during a surface attack. A British and a French submarine were also lost.

Despite these setbacks Lieutenant Commander Stoker planned his own attempt. Admiral de Robeck summoned Stoker to his flagship, Queen Elizabeth, and quizzed him as to how he proposed to overcome the hazards of the passage. Satisfied, the admiral said: “If you succeed, there is no calculating the result it will cause, and it may well be that you will have done more to finish the war than any other act accomplished.”

Two hours later Stoker had addressed the crew, stating that he would not think ill of any sailor who wished to withdraw. No one hesitated and all settled down to write what might have been their last letters to their families. The submarine was provisioned and was soon on its way from Mudros harbour on the island of Lemnos. Into the provisions went a case of vintage port – a sign of Stoker’s optimism for the mission.

In his autobiography “Straws in the Wind”, published in 1925, Stoker recalled how, the gravity of their circumstances notwithstanding, there was still ample room for humour when it came to allocating tasks in the capture of Turkey’s exotic capital: “The captain of the submarine was immediately to proceed in search of rare and priceless gems. The second officer was to inspect the ladies of the harem, during which process the third officer would engage the chief eunuch in polite conversation. That the fall of Constantinople did not take place may partly be attributed to the lack of patriotism of the third officer who, it is regrettable to have to record, showed a great distaste for the duty allocated to him.”

Stoker’s confidence proved to be well founded for on 25 April the AE2 was the first submarine to successfully penetrate the waterway and enter the Sea of Marmara. With orders from the admiral’s chief of staff to “generally run amok” inside Turkish territory, the AE2 operated for five days during which time she sank a Turkish cruiser and was a major distraction for the Turkish navy and the on-shore batteries. Mechanical faults eventually forced her to surface where she was damaged by the torpedo boat Sultanhisar.

Meanwhile news of the submarine’s success was spread to the soldiers ashore to improve morale. In fact the landing at Anzac Cove on 25 April had gone so badly that Lieutenant General Birdwood pushed for re-embarkation of his troops. News that the AE2 had successfully negotiated the minefield and entered the Sea of Marmara was thought to be a factor in the decision to persevere with the ground assaults. It prompted General Sir Ian Hamilton, who commanded the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force during the Gallipoli campaign, to send his famous message to the Australians: “…the Australian submarine has got up through the Narrows and has torpedoed a gunboat … You have got through the difficult business. Now you have only to dig, dig, dig until you are safe.”

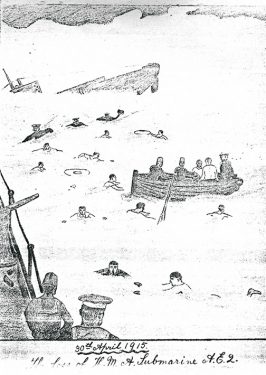

In the Sea of Marmara, with the hull badly damaged, Stoker ordered the boat’s company to evacuate and the AE2 was scuttled. All crew members survived the attack although four were to die of illness while in captivity. The AE2’s achievements showed others the task was possible and within months Turkish shipping and lines of communication were badly disrupted, with supplies and reinforcements for the Turkish defence of Gallipoli forced to take underdeveloped overland routes.

The AE2 was the only RAN vessel to be lost as the result of enemy action in World War I and, along with sister boat AE1, the total of the RAN’s operational losses in the war.

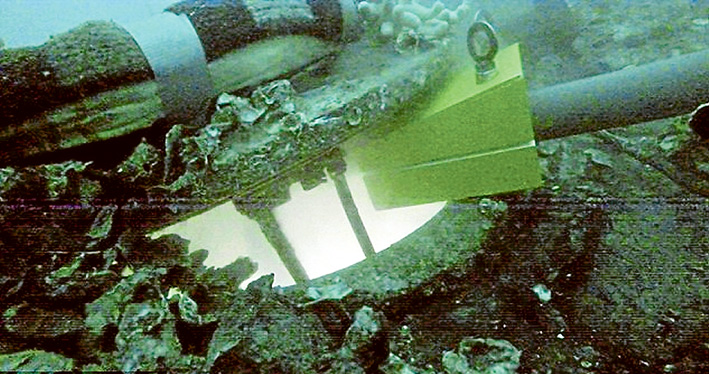

After several years of searching Selcuk Kolay, director of the Rahmi M. Koc Museum in Istanbul, located the submarine in June, 1998 lying in 72 metres of water. Several months later an Australian diving team confirmed the wreck as being the AE2. The submarine is not a war grave and the Australian government makes no claim to the shipwreck.

In September, 2007 a major marine archaeological expedition which included divers, scientists, physicians, filmmakers, photographers, journalists and archaeologists took place under the auspices of Turkish and Australian naval authorities. There were dramatic moments when a small camera was inserted into the submarine and observers were able to see the control room and living quarters.Notwithstanding a thorough search, no trace could be found of the case of vintage port; perhaps this was just a myth which enhanced the image of the colourful commander. The operation was closely supervised by “Bunts”, a two metre long conger eel which had taken up residence in the conning tower. The main objective of the undersea investigation was to determine if the AE2 could be raised and restored. Such a plan would have seen the submarine transferred to a viewing tank at Canakkale. Following the detailed inspection a recommendation was made against raising the wreck. Moving the submarine to a viewing tank, or alternatively relocating the wreck to shallower water, were advised against because of the estimated $80-100 million cost. Moving AE2 would also pose high risk to both the submarine and any vessels involved in the relocation; as well as potentially damaging the wreck there is an unexploded torpedo on board which would have prompted the investigators to suck in through clenched teeth. A subsequent workshop advised that the submarine be preserved through the use of sacrificial anodes to reduce corrosion, along with buoys and a surveillance system to mark the wreck and detect unauthorised access and potential damage. This work has now been carried out.

At a top level meeting of Australian and Turkish representatives held in Istanbul in April, 2015, the Australian delegation formally handed over documentation regarding the AE2 and official ownership of the wreck.

With the publicity surrounding the Gallipoli campaign in its centenary year of 2015, the deeds of Lieutenant Commander Stoker and his crew have also received recognition. In their writings historians and journalists have come to refer to the AE2 as “The Silent Anzac.”

So who was Leading Signalman Albert Thomson?

Albert Thomson was in fact born in Albury on 24 May, 1888. His mother did not survive the birth of her son and in the mid 1890’s his father returned to Scotland, taking Albert with him. In 1905 he left his job as a painter’s assistant to join the Royal Navy for 12 years service, signing on as a “boy, 2nd class.” He trained and qualified as a signalman on the Victory, and served on a number of RN ships, rising to Leading Signalman.

Thomson’s role as as leading signalman provided him with the nickname “Bunts” (from naval slang, “Bunting Tosser”) and in 1913, possibly because of his Australian roots, he volunteered for service on the new RAN submarine AE2. He was selected as one of the original crew and was officially on loan to the RAN for three years.

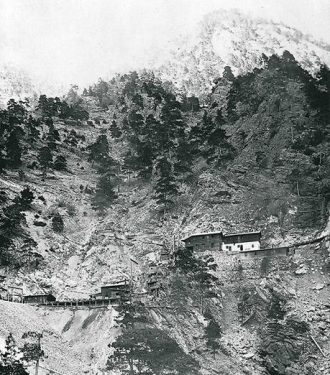

Thomson recorded the historic moment of the sinking of the AE2 in a series of graphic sketches which he drew later at prison camps, first at Afion Kara Hissar, then at Belemedik. At the latter, Thomson gained a reputation for stepping into fist fights to help AE2 comrades and by April, 1917 he had been transferred to a remote railway camp, possibly as punishment for fighting. Conditions there were appalling and Thomson and Bill Williams, also from AE2, tried to escape. In his secret diary Australian army corporal George Kerr recounted: “They spent all one Sunday night roaming the mountains until Bill Williams lost heart, to use Bunts’ words, and said it would be advisable to return … Bunts was cut up over Williams’ lack of courage, and says he tried to keep his heart up but all to no purpose.” (Williams, from Dunkeld in Victoria, died in mysterious circumstances while still a prisoner-of-war. He was one of four brothers; all enlisted but none returned.)

Not to be deterred, on 9 July, 1917 Thomson and Gwynne, also an AE2 submariner, made another escape attempt. Kerr wrote: “They set out nearly a month ago and had been gone a fortnight before the man in charge reported them missing. The Turks knew nothing for a long time (because) two men from the night shift (would) take their place for … counting … We (then) received news that they had been taken near Adana after having been seen wandering about for three or four days begging bread and water. Everyone believes them to be caught but they have not passed this way yet.”

After this escapade Thomson was returned to Belemedik and there were no further escape attempts recorded. After his release he returned to London on Christmas Eve, 1918. Despite being very thin, his physical constitution must have been strong for on 25 March, 1919 he re-enlisted for three years: this time with the RAN. These years were spent at shore bases Platypus and Cerberus. In 1920 he was joined by his wife Florence and son John who came out on the Zealandia. They set up home in Hastings where two more children-Ruby and Norman-were born.

On completion of his three years Thomson saw a business opportunity and obtained a bus, or more correctly a charabanc which may have been uncovered where the driver sat. The vehicle would be used to service the navy and the community. After surviving against terrible odds, Thomson died tragically on 29 May, 1922 when the bus overturned going around a corner in Hastings near where the Scout Hall is now situated. Apparently a wheel went into loose gravel and the driver was unable to regain control. A number of navy personnel on board were injured but Thomson was the only fatality. He was 34.

To compound the tragedy Norman, the youngest of the three children, was born on the day his father was killed. For some years the family battled on their large block in Hastings near where Coles is now situated. John, nine at the time, was taken in hand by the nuns and sent to the St Vincents orphanage in South Melbourne. He came home at weekends to help his mother with the cow and other chores. John eventually became a fitter and turner and lived in South Melbourne. He married Bessie and they had two children: John and Patricia. Ruby grew up in Hastings and married local boy, Ken Edwards. They farmed near Hastings and then moved to a Soldier Settlement block at Numurkah. Ruby and Ken had eight children and Ruby, now 95, lives in retirement in East Maitland. Norman spent his working life as a builder in Sydney and had two sons.

Albert’s widow, Florence, re-married, to Albert Bryant, a brother of Owen who was the grandfather of present Hastings resident, Max Bryant. Although some in the Bryant family believe Albert was the local policeman, others say that is a misconception as he was an MP during the war. Florence and Albert had no children but they did adopt a boy, Ron, who had a physical disability. Ron later owned the ice works in Hastings.

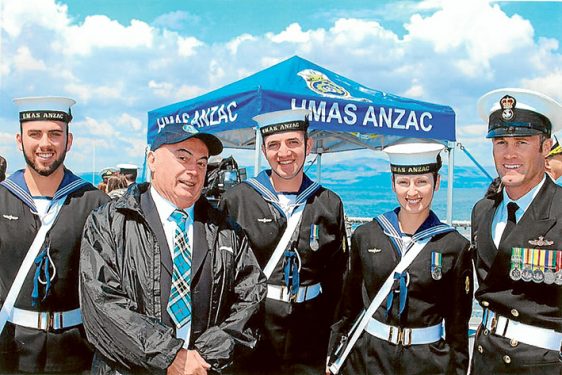

In an interesting third generation link John Thomson, the son of John and grandson of Albert, has been actively involved in the discovery of the wreck and the investigation of the proposal to raise the AE2 from the floor of the Sea of Marmara. Now 70 and living in Geelong, John recently indicated that he was pleased with the decisions made and work carried out by the authorities. One of the highlights of his involvement was seeing his grandfather’s sandshoes neatly stacked in the flag locker in the conning tower. It would not be hard to guess who provided the name “Bunts” for the resident conger eel! It was John, together with Barry Edwards, a son of Ruby, who was responsible for the installation of the tombstone in the Hastings cemetery. Location of the grave site was difficult and the error with the name is explained by the fact that an alteration was made on the birth certificate creating some confusion. However the man in question was always known as Albert or, more commonly, “Bunts.”

Dacre Stoker: Larger than life

Henry Hugh Gordon Dacre Stoker was born in Dublin, Ireland on 2 February, 1885 to Dr. John Stoker and his wife, Jane. The “Dacre” was hastily included in the name when the child’s wealthy godfather threatened to cut him from his will if his existence was not recognised. As it turned out, the godfather ventured to South Africa to dabble in diamonds and was not heard from again. The godson, however, took a fancy to that name and was generally known as Dacre for the rest of his days. Also of family significance was that the Irish novelist Bram Stoker, who wrote the 1892 Gothic novel “Dracula”, was a cousin.

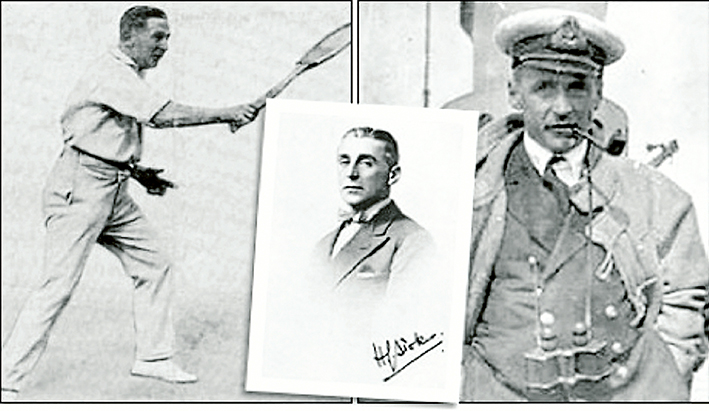

Although his family included many doctors, at the age of 12 young Dacre decided on a career in the navy and in 1900 he joined the Royal Navy as a 14-year-old cadet. While an average student, Stoker did excel at sport, particularly rugby, hurling, polo and tennis. He competed at Wimbledon several times, winning the doubles one year against a Spanish pair. Stoker played tennis until well into his 70s.

Dacre Stoker was promoted to midshipman (1901) and then sub-lieutenant (1904). After service in the western Atlantic he became interested in in the submarine service – a relatively new branch of the navy. This was at a time when not everyone was in favour. Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson’s famous comment that they were “underwater, underhand and damned un-English” summed up traditionalist naval suspicion that there was something sinister and sneaky about “submersibles”, as they were then called. Sneaking up on the enemy from behind was just not cricket, old chap. In fact Wilson also sniffed that submariners caught in wartime should be hanged as pirates. These were the times in the Royal Navy when it was said that “captains spoke only with admirals and admirals spoke only with God”.

Stoker found it difficult to maintain his lifestyle on a Sub-Lieutenant’s pay of five shillings a day; as a submariner he would receive an additional six shillings a day. This was sufficient incentive and he started training in October, 1906. Two months later he was promoted to Lieutenant.

Dacre Stoker was very much a free spirit and reveled in the freedom that the submarine service offered. He was given command of a submarine in January, 1909 and in 1913 he volunteered to serve on loan with the RAN as commanding officer of one of its new submarines. By this time he was infatuated with polo and the reason for his transfer was information that in Sydney there was a rich man who would pay all your expenses if you’d only go and play polo with him. Although the “rich man” never materialised, it marked the beginning of his association with HMAS AE2 which came to a dramatic conclusion with its sinking on 30 April, 1915.

For the next three and a half years Stoker, who had been promoted to lieutenant commander in December, 1914, was held in the various Turkish prisoner-of-war camps where he used his acting talents to entertain fellow prisoners. In March, 1916 he escaped and was on the run for 18 days before he was recaptured and imprisoned in Constantinople. Stoker was repatriated to England in December, 1918, reverted to Royal Navy service, and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order in 1919: “In recognition of his gallantry in making the passage of the Dardanelles in command of HM Australian Submarine AE2 on 25 April, 1915.” Many considered that the Victoria Cross would have been more appropriate as it had been awarded to three other captains of Allied submarines.

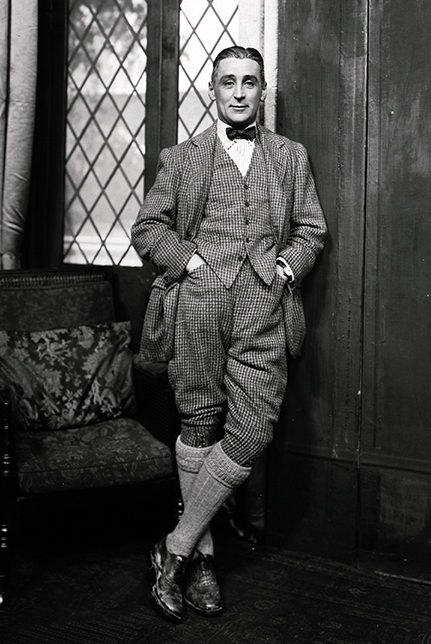

Although promoted to commander in 1919, Stoker chose to leave the navy in the following year; he had always been a keen amateur actor and playwright and now pursued his second career. As an actor Stoiker was successful on the stage in both Britain and the United States. He often played the part of a professional such as a military officer or a doctor. By the end of the 1920s Stoker was a regular and popular performer in West End plays and in 1932 started radio broadcasts of short dramatic stories. In 1933 he made his first cinema appearance in the movie “Channel Crossing”. In 1935 he played the part of a naval officer whose ship was sunk in action in World War 1 in the movie “Brown on Resolution.” Overall Stoker appeared in eight films from 1933 through to 1948 and was credited as H G Stoker or Dacre Stoker. His contemporaries included Sir Laurence Olivier and Sir John Mills. He was also the business manager of the Apollo Theatre. His autobiography “Straws in the Wind”, which was largely about his adventures on the AE2, was published in 1925.

When war broke out in 1939 Stoker was recalled to the Royal Navy. With the rank of acting captain he served in a variety of capacities from being in command of a coastal services base, to public relations officer in the Admiralty, to being involved in the planning for D-Day. He retired again in late 1945 and returned to his life as an actor and playwright.

Dacre Stoker became involved in early television dramas in the 1950s but, now well into his mid-60s, he began to take life a little more quietly and devoted additional time to sporting pursuits such as golf, tennis and, particularly, croquet which he found attractive to his ageing limbs. While one critic of that era described croquet as an “…impossibly difficult exercise played to incomprehensible rules by venomous old people with a tendency to swear”, Stoker was fascinated by it. In fact in 1962, at the age of 77, he became the croquet champion of Ireland. He was also a member of the exclusive Garrick Club for gentlemen associated with the theatre in London’s West End.

Lieutenant Commander Stoker died in London on his 81st birthday on 2 February, 1966.