OBITUARY

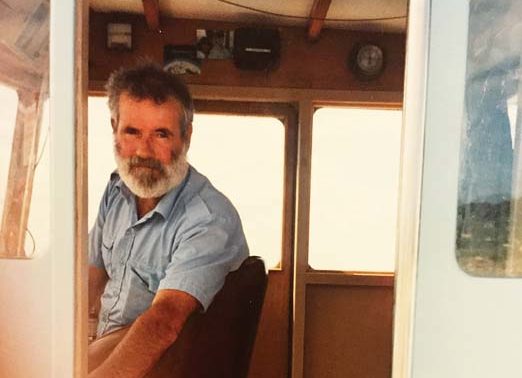

Anthony (Tony) Muir, 1943-2017

Master mariner, diver

SOMETIME over the next few weeks a flotilla of small boats will sail towards Port Phillip Heads.

It will be spring, a time of renewal, regeneration and hope. Those on board the boats will look toward the Polperro, because it will be from the deck of his beloved timber vessel that the ashes of Tony Muir will be consigned to the waters that he loved.

Tony Muir died on 4 July, less than one month after celebrating his 74th birthday. He had been diagnosed with cancer a decade earlier.

Hundreds attended a funeral service for Muir at Badcoe Hall, Point Nepean, on 23 July.

Muir lived his life and earned his living in and around the sea. A diver and sailor, he’d worked and sailed overseas and throughout Australia, most recently with the Sorrento-based family business, Polperro Dolphin Swims.

In its earlier days Polperro – built in 1979 by the boat-building Pompei family of Mordialloc – had been a dive boat in Bass Strait, with Muir carrying scientists and workers to the islands dotting the strait between Victoria and Tasmania. Regarded by many as a treacherous stretch of water, Bass Strait was like a second home to Muir and he revelled in its many moods.

Tales of the sea and those who sail it are the stuff of legend. Tony Muir wasn’t a legend in the same way that Ulysses is mythologised or the fictional Captain Ahab’s pursuit of a white whale has become legendary, but he was the real thing: a man of the sea.

However, with his death Muir is likely to become the stuff of legend. It’s a status he will have earned and have bestowed on him through his deeds, devotion and determination.

He was born in Richmond and grew up in South Yarra. As a boy he roamed the banks of the Yarra River and sailed at Albert Park.

In the words of Judy, his wife of 54 years, Tony Muir was a handsome wild man, an adventurer, a dreamer. But he had an introspective, deeper side that steered him towards reading books and poetry: Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and Keats, Masefield, Tennyson and Gordon. He wrote poetry and sketched.

He cherished wooden boats and Judy Muir describes how early in their relationship they embarked on a 15-month journey in a 5.3 metre yacht which had a main sail and a jib but no motor.

“Well, it truly is now the ghost and Mrs Muir,” began Judy Muir’s the eulogy for her husband.

“Tony was a pioneer. He dived deeper, he flew higher and he lived on the edge, always. He stood by in [battled] heaving seas when an oil rig needed to be evacuated,” Judy Muir told the packed Badcoe Hall. “The vessel’s doors had blown in with wave impact, his crew were all down and the seas were of nightmare proportions.”

He had rescued others in other desperate situations as well as saving himself after losing his breathing apparatus while underwater “but still had the presence of mind to survive by remaining calm”; he was badly burnt when a vessel capsized, later returning to Singapore with blackened skin.

“In an emergency, Tony was wonderfully calm and oh-so capable. He made us safe,” Judy Muir recalled.

“Tony’s love and loyalty to family was fierce, his friendships steadfast and he extended care to all those who came into our sphere.”

As well as their own three sons – Troy, Ben and Angus – the Muirs “adopted”, or roped in, to make an analogy using one of Tony’s favourite things, any number of people into their extended family. As a sailor and diver Muir knew all about the value of ropes and splicing was a favourite pastime.

Like his linguistic skills, Muir used rope as medium with which to build friendships and form relationships. It transcended generations and handing out rope to young passengers or using it to tie gift parcels became a trademark.

It is also a tradition taken up other families close to the Muirs.

Muir was proud of their Blairgowrie home, Cootehill, but also relished its self deprecating nom de plume, Casa del Whacko.

“He just rolled with the changes and cooked, cleaned and did what dads do regardless of whether you were kith or kin. People mattered. No one was judged, everyone was well-fed,” Judy Muir said.

As his health declined and he was unable to speak, the community within which Tony Muir lived started to give back. Shopkeepers on both sides of Port Phillip (Sorrento and Queenscliff) knew what he wanted without the need for words and those working with him could only imagine the frustration he felt at not being able to chastise a stubborn piece of machinery. “Swear words were etched pages deep as he cursed,” Judy Muir said.

Up until two weeks before his death he would still go out in his dinghy – fitted with just one comfortable seat, which gave a big hint that he cherished being alone – and Judy Muir would get calls from ferry skippers assuring her that they’d “seen Tony and he’s all right”.

Even when ill, practicality would take over. Long-time friend Will Baillieu tells of Muir being “rushed” to hospital by an ambulance that became bogged in the driveway at home.

While the paramedics were scratching their heads, Muir calmly let himself out of the ambulance’s back door, walked up the steep drive and returned with his own four-wheel drive.

After pulling the ambulance free he returned his own vehicle and then let himself back into the ambulance for the trip to hospital.

Muir’s linguistic skills (being able to listen to the SBS news in Arabic or speak to ships’ crews in their own language) were mirrored by his ability to master the intricacies of machinery. He seemed to relish getting stuck in the mountains with a broken-down vehicle. As son Troy put it: “It wasn’t so much the adrenaline rush he chased as it was about savouring the aftermath.

“He had a mind inclined to understanding moving parts and an acumen honed by necessity as he worked in remote places where there was no one to call if you had a problem.”

He was an understanding father and if one or other of his sons wasn’t quite up to fixing a particular problem, he would “encourage other talents like torch-holding, tea-making and recovering dropped bits from the bilge”.

“There is an old Viking belief that you live on as long as people speak your name in stories and I reckon we’ll be speaking about Tone for a long time to come,” Troy Muir said.

Ben Muir remembered their family life as never having a dull moment, with his father “always tinkering away at some project whether it be boats, ropes or engines”.

Their “adventures” included camping in the Olgas (Kata Tjuta), cruising the Murray River in a tinny, and island hopping around Bass Strait.

His wife Judy and their sons Troy, Gus and Ben were with Tony Muir the night he died.

Troy described his father as having “slipped his mooring for his last great adventure – with bravery and grace”.

On a fine day in the coming weeks that mooring will be slipped by his family and friends as they take Tony Muir on one last voyage in the Polperro, towards The Heads.

First published in the Southern Peninsula News – 26 September 2017