ABOUT 300,000 Australians volunteered to serve their country between 1914 and 1918; this from a nation of fewer than five million people. Most saw service on the Western Front: in Belgium (Flanders) or along the River Somme in France. About 52,000 died and are buried there.

In the postwar years in Australia, whenever a new area was being developed it was common, almost mandatory, to honour our war dead by naming the streets after famous Western Front battles in which Australians had participated.

The trapezium-shaped area in Bittern bordered by South Beach Rd (to the west), Disney St (south), Trafalgar St (north) and the railway line (east) is fairly typical. However an examination of the names selected by the developer at the time leads one to ask “What was he thinking?”.

There are 11 streets in the subdivision. One (Centre Ave) has geographical rather than historical significance; for the purpose of this exercise we can discard it. Of the remaining 10 streets, only six relate to battles of some significance and two are of only minor interest to the AIF. Let’s have a look at each in turn.

1. POZIERES ST

This is a worthy inclusion in the developer’s selection. The Somme offensive started early in July 1916 with no significant progress. The key to the German defences was the village of Pozieres on the Albert-Bapaume Rd. The British Major-General Walker decided to use the Australians (1st, 2nd and 4th Divisions) and the New Zealand Division to spearhead the attack on the night of 23 July 1916. The attack was a success but the Germans, recognising the critical importance of the village to their defensive network, attempted to retake Pozieres on 7 August following a particularly heavy bombardment. The Germans overran the forward Anzac defences, and a wild melee developed from which the Anzacs emerged victorious.

The Anzacs then drove along the ridge towards Mouquet Farm. After heavy fighting, they were relieved by the Canadians who captured Mouquet Farm on 26 September 1916.

The Anzacs then drove along the ridge towards Mouquet Farm. After heavy fighting, they were relieved by the Canadians who captured Mouquet Farm on 26 September 1916.

In the fighting at Pozieres and Mouquet Farm, the Australian divisions suffered more than 23,000 casualties of which 6741 were killed.

Australia’s most decorated soldier, Captain Albert Jacka of the 4th Division, who had won the Victoria Cross at Gallipoli, won the Military Cross at Pozieres and another the following year at Bullecourt (see below).

At the conclusion of the war, each of the five Australian divisions was permitted to select an area to erect a memorial to commemorate its achievements; the 1st Division memorial is at Pozieres.

2. BULLECOURT RD

This, too, is a worthy selection. On 9 April 1917 the British Army started the significant Battle of Arras. It incorporated the smaller battles of Vimy Ridge, which the Canadians commemorate, and Bullecourt, with which the Australians identify.

Four experienced Australian divisions (1st, 2nd, 4th and 5th) were part of the British 5th Army under General Sir Hubert Gough, a comparatively young but energetic commander. Gough wanted to attack at Bullecourt to support the British 3rd Army offensive to the north and the French to the south.

The general’s aggressive attitude, coupled with poor planning, resulted in heavy losses. His attack launched at Bullecourt on 11 April 1917 was a disaster. Despite this, a further attack across the same ground was ordered for 3 May. The Australians broke into and took part of the Hindenberg Line but no important strategic advantage was gained; in the two battles the AIF lost 10,000.

In the first battle, Gough employed a dozen tanks, a fairly recent innovation, to lead the troops with disastrous results: the tanks were destroyed and the soldiers took an instant dislike to them, believing that they only attracted machine gun and artillery fire. While 3000 were killed or wounded in the first battle of Bullecourt, 1170 Australian soldiers were taken prisoner; the largest capture of Austra-lian soldiers until the fall of Singapore in 1942.

In front of the Bullecourt church is a memorial to the Australians unique on the Western Front: the focal point is an original slouch hat, bronzed to protect it from the elements.

3. MESSINES RD

This is also an essential selection. The battle of Messines, fought on 7 June 1917, was the first large-scale action involving Australian troops in Belgium and also marked the entry of the 3rd Division into a major battle. The major offensive by the British, launched on Messines Ridge, south of Ypres, was intended to retake the areas lost in the First and Second Battles of Ypres. This was an important success for the British Army leading up to the beginning of the Third Battle of Ypres several weeks later.

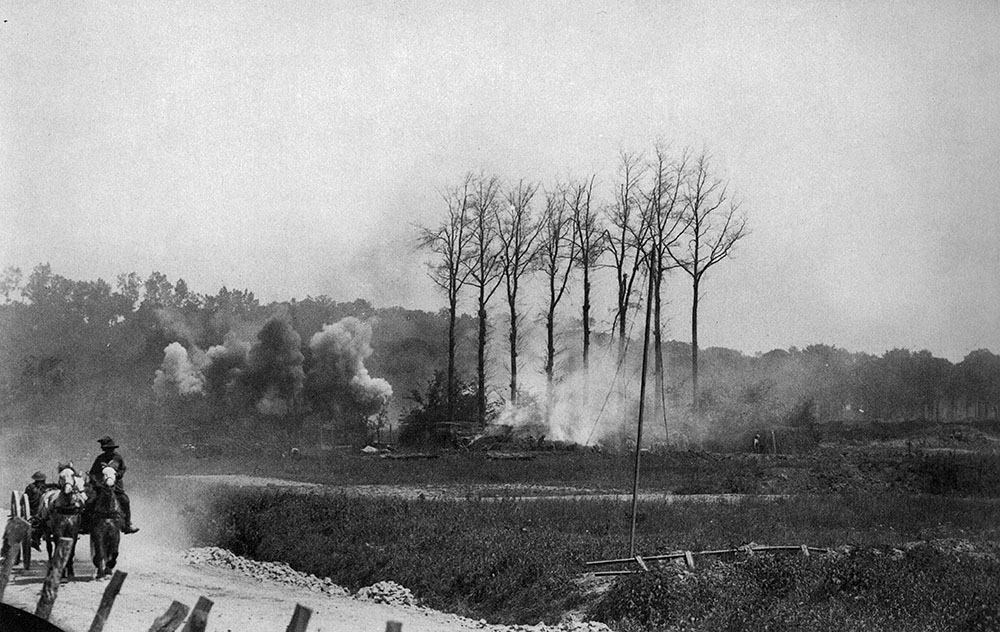

Since 1915, specialist tunnelling companies including more than 30,000 men, many Australian, had been digging tunnels under Messines Ridge and about 500,000kg of explosives had been placed. The First Australian Tunnelling Company had been particularly active at Hill 60 near Ypres since November 1916. Occasionally Allied or German miners would dig into an enemy shaft and ferocious hand-to-hand fighting would break out in the cramped tunnels.

At 3.10am on 7 June 1917, 19 powerful mines exploded under the German trenches, killing 10,000 Germans. The explosion was apparently heard in London and detected on a seismograph in an observatory on the Isle of Wight. Heavily supported by great volumes of artillery fire, the troops, commanded by General Sir Herbert Plumer, surged forward to capture the enemy positions. The 3rd Australian Division, under General John Monash, was anxious to prove itself worthy of the other veteran Australian divisions.

While the older Australian divisions were being mauled on the killing fields of the Somme, the 3rd Division was always training or in reserve. The veterans were somewhat dismissive of the 3rd as a consequence, referring to them as “the neutrals”. Accordingly, the 3rd Division had a point to prove.

It made a successful attack alongside the NZ Division south of Messines village. The other Australian division involved, the 5th, made a follow-up attack later in the day. Although some fighting continued, the result was virtually decided by the end of the first evening with the ridge being taken and enemy counter-attacks repulsed.

On 11 July, however, the Germans retaliated with an awful new weapon – mustard gas.

Beginning in late July 1917 and continuing into October, the struggle around Ypres was renewed with the Battle of Passchendaele (technically the Third Battle of Ypres, of which Passchendaele was the first phase). Canadian veterans from the Battle of Vimy Ridge (see below) joined the depleted Anzacs and British forces and took the village of Passchendaele on 30 October despite extremely heavy rain and casualties. Both sides lost a combined total of more than 500,000 men in the offensive. Australians also contributed to the Third Battle of Ypres when they attacked along the Menin Rd and at Polygon Wood, so named for its unusual shape It is the site of the memorial to the 5th Division.

Even nowadays, long after hostilities ceased, one or two farmers in France and Belgium unearth unexploded bombs every year, often to their extreme detriment. The residents of Messines are walking on eggshells; according to legend there were 20 mines under the ridge but only 19 exploded. No one is sure where number 20 is located.

4. PERONNE ST

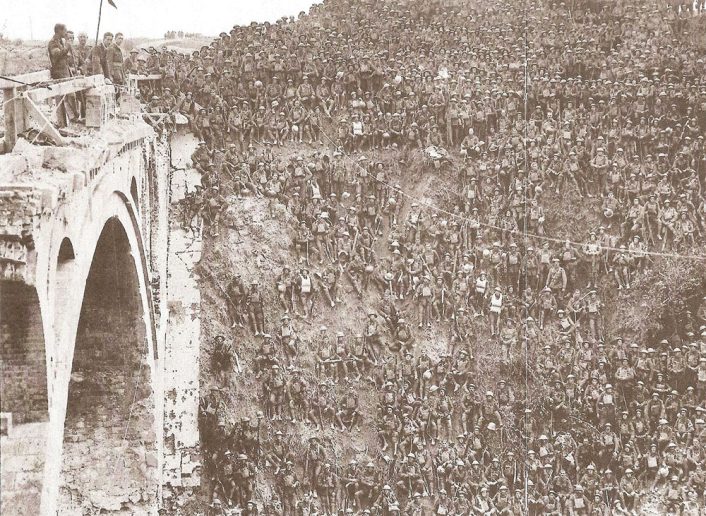

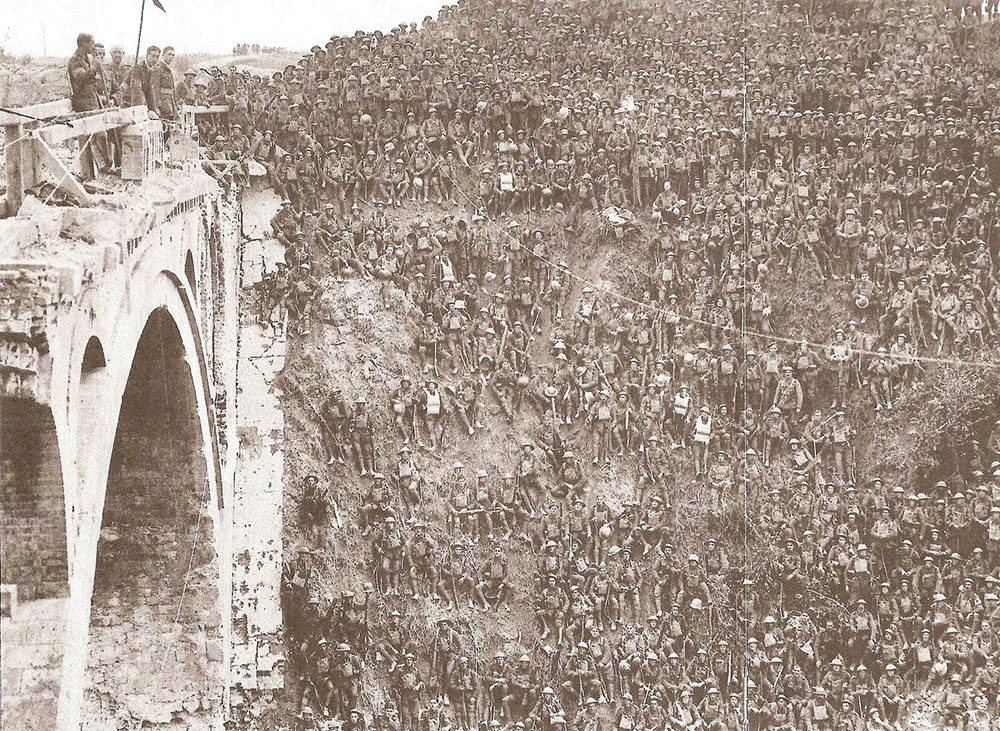

This is almost a compulsory inclusion. The end of August 1918 found the German troops at their last stronghold at Mont St Quentin overlooking the Somme River and the town of Peronne. Mont St Quentin stood out in the surrounding country, making it a perfect observation post and a vital strategic area to control. General Monash was keen to capture this strategic post and the Australian operation is sometimes regarded as the finest achievement of the AIF.

The 2nd Division crossed the Somme on the night of 31 August 1918 and attacked Mont St Quentin from the unexpected position to the north-west at 5am. By 7am the Australians had gained the village of Mont St Quentin and five German divisions had become confused and dispersed, or had fled. By midnight 31 August, Monash’s troops had taken 14,500 prisoners and 170 guns since 8 August. Allied troops also broke through lines to Peronne by 8.20am on 1 September 1918.

The Germans counter-attacked with much hand-to-hand fighting in Peronne. The outnumbered Austra-lians were pushed back but, when relief battalions arrived, they regained lost ground but at a cost of 3000 casualties. By the night of 3 September the Australians had secured Peronne.

Private Alex Barclay of 17th Battalion was shot in the head by a sniper duting the Mont St Quentin attack. Miraculously the bullet passed through his skull and he survived to re-enlist in the Second World War.

The 2nd Division selected Mont St Quentin as the site for their divisional memorial. Unveiled in 1925, the memorial was more elaborate than the other four, which are identical stone obelisks. It showed an Aus-tralian soldier bayoneting a German eagle sprawled at his feet. Not surprisingly, it was removed by the Germans when they occupied France in 1940 and was apparently melted down. A less controversial sculpture of a Digger in full kit replaced it in 1971.

5. VIMY ST

At this point the puzzlement in Bittern starts. Vimy is six miles north of Arras, and between 9-12 April 1917 the Canadian Expeditionary Force was heavily engaged with three divisions of the German 6th Army. It ended when the Canadians took control of the German-held high ground along an escarpment at the northernmost end of the Arras offensive. At the same time the Australians were heavily involved at Bullecourt.

Vimy Ridge is the site of the Canadian National Memorial, perhaps the grandest of all battlefield memorials.

6. BAPAUME AVE

This is another curious choice. In mid-March 1917, the German army withdrew from the Somme to the Hindenberg line. It destroyed Bapaume before withdrawing and the Australians entered with a band playing and without a fight on 17 March 1917.

Bapaume was, however, reoccupied by the Germans during their big advance of early 1918 and this led to the “second” battle of Bapaume between 21 August and 1 September 1918, which was the second phase of the Battle of Amiens. The town was recaptured by the New Zealanders on 24 August while the Australians were pre-occupied further south taking Mont St Quentin and Peronne.

The Germans left plenty of booby traps for the Australians when they occupied the town after the first “battle”, including a delayed action device that obliterated the Bapaume Town Hall, one of the few buildings left standing. Unfortunately a number of Diggers had decided that it would be an appropriate place for a rest and the explosion killed 26.

7. ANCRE AVE

At this point it becomes harder to justify name selection. The Ancre is a river in Picardy that flows into the Somme at Corbie. The British 5th Army did fight a Battle of Ancre between 13-18 November 1916 as the final act of the Battle of the Somme. The Australians, however, were involved in heavy fighting in the area on 27 March 1918 and, as a consequence, the 3rd Division war memorial is located in open country between Sailly-le-Sec and Mericourt-L’Abbe, two villages in the Ancre River valley.

8. LILLE ST

The magnificent view from the heights of Vimy Ridge (see earlier)is over the wide Douai Plain and the then-great coal mining region of northern France centered on Lille. Clearly seen from the ridge is the famous Double Crassier, a huge twin-peaked slag heap, evidence of the extensive coal mining past in the area. For much of the war the Germans occupied this industrial heartland of France and made use of its natural and human resources. There appears to be no grounds for Lille to be selected as one of the subdivision’s street names.

9. LENS ST

Lens was a small village located between Vimy Ridge and Lille. It was obliterated during the ebb and flow of battle, and there would appear to be no good reason for it to be included as a Western Front battlefield town.

10. OSTEND ST

This is the final absurdity as the seaport of Ostend was in German hands for all but the closing stages of the war, and was used as a submarine base. It has no significance as far as Australia is concerned.

So there it is: four street names that merited the honour, two which were borderline, and four that couldn’t really be justified. What of the places that were passed over?

PASSCHENDAELE

A major battle for the AIF (see earlier) and the final phase of the vital Third Battle of Ypres. Perhaps it was too hard to spell?

YPRES

The Australians played a significant role in the final defence of “Wipers”, as they called it. Perhaps it was too hard to pronounce?

VILLERS-BRETONNEUX

The most “Australian” of all the villages with the Victoria School (paid for with funds donated by Victorian school children) and its sign “Do Not Forget Australia”, streets named Victoria and Melbourne, and the Cafe Kangaroo. It was where the Australians stopped the German advance on the already significant day of 25 April 1918, and is the site of the main Australian war memorial. Perhaps it was too cumbersome for a street name?

AMIENS

This was a major railway junction, just as Lille was for the Germans. To have lost this stronghold during the German spring offensive of March-April would have been catastrophic and underlines the importance of the Australian victory at Villers-Brettoneux, which is located only 16km to the east.

HAMEL

In a meticulous action on 4 July 1918, Monash ensured close co-operation between infantry, tanks, artillery and aircraft in a battle used as a template for British attacks for the rest of the war. Monash intended the battle to take 90 minutes; it took 93! Ironically the attack was carried out by the 4th Division, the very division that had developed an intense dislike of tanks at Bullecourt. This all changed when they were properly deployed at Hamel.

FROMELLES

This was Australia’s initiation to the horrors of the Western Front. Poorly planned and poorly executed, this “diversion” saw the 5th Division suffer 5533 casualties in 24 hours. A new cemetery was created at Fromelles in 2010 to inter about 400 Australians who had been buried nearby in a mass grave at Pheasant Wood. Fromelles is also the location of the famous “Cobber” statue. It depicts Sergeant Simon Fraser carrying a wounded comrade to safety. During one of several trips into no man’s land (disputed territory), Fraser heard a week voice call out “Don’t forget me, cobber.” The expression came to symbolise the bond of mateship that held the Australians together in those terrible days.

HARBONNIERES

This was where Australian soldiers contribution to the greatest single day’s advance by Allied troops in the entire war – 8 August 1918. It was dubbed “the Black Day” by General Ludendorff and led to German capitulation three months later.

ALBERT

Australians saw a lot of this town as it was the main British base of operations during the Somme battles. Before the war it was a pilgrimage site as the magnificent basilica in the main square was topped by a gilded statue of the Madonna holding the baby Jesus to the heavens. By 1916 German artillery had damaged the basilica and the statue was leaning precariously from the tower. For the next two years the “Leaning Virgin” was one of the most iconic landmarks of the Western Front.

One myth, believed by the British, was that when the statue eventually fell, the war would end. In fact Bri-tish artillery destroyed the tower early in 1918 when the Germans briefly occupied Albert, but soldiers who saw the fall of the statue were disappointed – the war ground on for another eight months. Australians fighting around Albert thought the leaning statue resembled a swimmer leaving the blocks; with more than a touch of irreverance, they referred to it as “Fanny Durack” who was an Australian swimming champion of that time.

MONTBREHAIN

This was the AIF’s final battle in the closing weeks of the war and was where one-time Hastings resident George Mawby Ingram won his Victoria Cross. It is also the location where the 4th Division has its memorial.

It’s hard to believe that the Bittern developer, faced with such a huge range of options, could have chosen so poorly.