OF the 120 listed on the honour roll in Mornington’s Memorial Park, a number were decorated for bravery under fire. One of those was Robert Bates of the Australian Army Medical Corps who returned home with a Military Medal (won at Lone Pine) and Bar (won at Pozieres.) What makes his record different to the other 119 is that he was a pacifist and never fired a shot during his years of service.

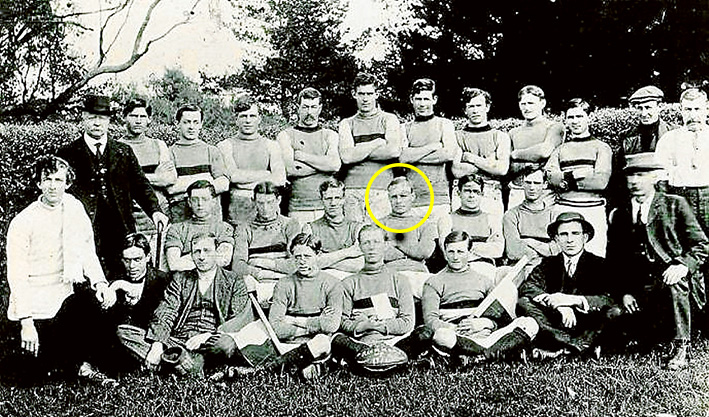

ROBERT Bates was born at Kew in 1887, the only son of Alfred and Isabella (nee Bartlett). The war was only a few weeks old when Robert enlisted on 19 August, 1914; his serial number was 375. During 1914 he had been an integral team member of the Mornington Football Club which finished the season as runners-up to Hastings. Although the family address was “Una”, The Esplanade, Mornington, Robert’s occupation was shown as “grazier” on the electoral roll as the family owned a farm at Moorooduc. However at the time of his enlistment Robert was training for the priesthood at the small Anglo-Catholic St. John’s College in Melbourne; accordingly his enlistment papers state his occupation as “student.”

On 21 October, 1914 he sailed on HMAT A20 Hororata as a member of the Australian Army Medical Corps attached to the 7th Battalion. Robert Bates took part in the Gallipoli landing and was awarded the Military Medal for his bravery at Lone Pine. The citation, published in the London Gazette on 27 October, 1915, read:

The enemy was heavily bombing the position all night. The stretcher-bearers were kept busy evacuating the wounded and Private Bates had. in consequence to do practically all the work of bringing the wounded under cover from the firing line and rendering first aid.

He carried out this work repeatedly and fearlessly under very heavy bombing.

During the enemy’s counter attack on the morning of the 9th August, 1915, Private Bates continued the same work while the attack lasted.

Promoted to corporal, it was not long before Bates was in action in France where he was awarded a bar to his Military Medal. The citation, published on 21 August, 1916 read:

In trenches N.E. of POZIERES, FRANCE on the 21st August, Cpl BATES attached to 7th Bn showed conspicuous bravery during the fighting around POZIERES. He continuously by his calmness and coolness under very heavy shell fire stimulated over-excited men to return to their duties in the line. He has shown excellent work with the Battalion from the time of its formation and has never missed a day from it during the day of the 21st. He under very heavy shell fire went out into No Mans Land and read the burial service barehanded, over a fallen Comrade and beside those he was unable to bury placed a wooden cross, bearing their names and particulars concerning them.

He remained in No Mans Land over one hour and during the whole time the enemy’s shelling was extremely heavy.

In the opinion of one Anzac officer, expressed in London Opinion and later in The Mirror of Australia on 24 February 1917, a Victoria Cross would not have been out of place:

I’ve pretty well given up belief in miracles; but this war has raised a lot of ghosts, and among them the ghost of a belief that perhaps miracles are among the things that happen, even in an artillery duel.

When we went into action, I was securely placed behind a ruined farmhouse; but some German must have seen the Red Cross flag, for a shell sent the ruins in 5000 different directions, and I found myself dressing wounded in a moving sea of sand; that’s all I could call it.

We had fought at Pozieres for 24 hours, and boys from every part of Australia had formed up, marched out, doubled, and gone to death, like men that they were; and now it was the cold grey dawn of a new day, and from every crater and hole came the groans of the dying, and all between were huddled masses of khaki that never moved, and over it all the winter sun began to rise.

Little Bates had worked with a will; a queer little fellow, and a Quaker who would not fight. But he carried in man after man, and tended them, and there were a few chaps who said that he had prayed over them. I don’t know. I hadn’t time to straighten my back to see. All I know is, that as Christ walked the Sea of Galilee, so Bates walked No Man’s Land in the light of that winter sun rising over the hell made by man.

In one hand he held a bundle of wooden crosses, and in the other a flask. Over each wounded or dying man he bent and put his flask to his lips. On the breasts of the dead he put a cross, and when he could he made a hollow in the sand, and covered the corpse, and in every case, not much less than a hundred all told, he said a prayer and committed to its God the soul that was taking its flight.

Through all that hellish artillery fire, those screaming shells, and bursting shrapnel, he moved, a silent Christ. The Chaplain came and stood by me, and his fingers shook as he pointed to him.

“I would give all that I care for in the world to have the courage of that man. I have served my God for 40 years with all my heart and mind, and a boy comes out of a Quaker home and shames my faith.”

I don’t know whether Bates got the VC I reported fully about him, but somehow it does not seem to me to matter very much for such a man. He can afford to wait for the judgement of the King of Kings.

On 14 November, 1916, soon after he was promoted to sergeant, Robert Bates was severely wounded on the Somme with gunshot wounds to the knee and arm. He was repatriated to England where he underwent a long period of rehabilitation. In 1918 he took extended leave to take up an Overseas Sailors’ and Soldiers’ scholarship, studying theology at Merton College, Oxford. He obtained honours and on 19 June, 1920 he left England on the Orontes, disembarking in Melbourne on 1 August. The final entry in his military record shows that he was discharged from the AIF on 9 December, 1920: “Medically Unfit-Disability-GSW Rt. Knee.”

Early the following year Robert Bates went back to England and in 1922 he became the curate at St. Andrew’s, Bethnal Green in the poor East End of London. In 1924 he returned to Australia to become the vicar of Copmanhurst in the Grafton Diocese but two years later he was appointed the rector of All Saints, Wickham Terrace, Queensland. He carried out these responsibilities until 1947. During this time he held the position of chaplain-general of the former Brisbane Franciscan communities and of St Christopher’s Boys Farm School which he established and continued to manage after retiring from his post as rector at All Saints. His farming background was put to good use and his stud Ayreshires won prizes at agricultural shows. Subsequently a chapel was erected in his honour in 1971 at the Brookfield Centre for Christian Spirituality in Kenmore Hills, Queensland.

Robert Bates married Clarice Mary Albina Cox in 1942; Clarice was one of his choir girls and had been practising as a dietitian in Brisbane. The Rev Robert Bartlett Bates died 27 June, 1955, aged 68.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”20″ gal_title=”Robert Bates – ANZAC”]

Acknowledgement: In 2015 Val. Wilson OAM of the Mornington and District Historical Society published “The Names on the Mornington Honour Roll 1914-1918. Who Were They?” I am indebted to Val for allowing me to borrow from the entry on Robert Bates. Copies of her most informative book are available from the Society for $20. Thanks also to Val Latimer of the Mornington Peninsula Family History Society for her assistance.

First published in the Mornington News – 19 April 2016