IN his book “Those We Forget”, published in 2014, David Noonan comments on the “casualties” which occurred after the cessation of hostilities in 1918 amongst the AIF men who were wounded or gassed: “… it is estimated that they now number 62,300 (plus or minus 400), about 550 by their own hand, mainly in 1919 and 1920, and a further 8000 men would die a premature death due to war-related causes in the post-war years.”

In 1918 an entire government department – subsequently the Department of Veterans’ Affairs – came into being in Australia to try to look after those who were carried or had managed to walk or hobble home. The first artificial limb factory was opened at the Caulfield hospital in Melbourne. Eventually, Australia had six of these factories.

Thousands of men ended their lives in sanatorium wards or boarding houses, still coughing from the gas. Peter Synan’s “The Dahlsen Story – A pioneering Family in Gippsland since 1862” provides an excellent illustration of the fate that befell some of those who returned. Fred Dahlsen enlisted in April, 1915 and saw service at Gallipoli and the Western Front. Debilitated by illness and the trauma of war, Fred was hospitalised for some time before returning to Melbourne in October, 1918. “There was no hero’s return to his home town of Bairnsdale for him, as he chose to withdraw to Acland Street, St Kilda, his mother’s residence. Although not officially declared ill or unfit, war it seems had worn him out, sapped his spirit. He retired from workaday life and is remembered by family as a pathetic figure, sitting huddled in the billiard room listening to a crystal radio set with his headphones, his social outings confined to a nearby hotel. Yet this was a man of Gallipoli and Fromelles, the legendary defeats which had forged so much of the self-image of the young Australian nation.”

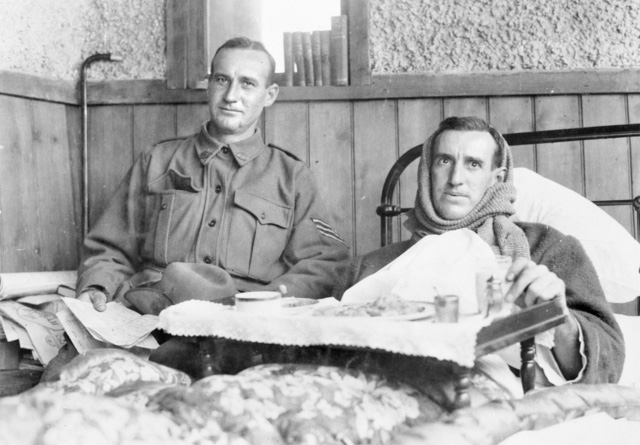

Arthur Dahlsen, Fred’s older brother, enlisted in October, 1916. He joined the 8th Light Horse but his war was brief and tragic . He suffered a number of illnesses as well as a bullet wound to the back and neck, and before Christmas 1917 he was back in Melbourne on the hospital transport Wiltshire. Synan tells us: “He was too ill to return to his previous work in the family store in Bairnsdale. Soon he was thoroughly incapacitated, becoming a bed-ridden patient in turn at the Caulfield Military Hospital and Anzac Hospital. Despite being treated by the best specialists, Arthur died in October, 1920. It had been a thoroughly wretched war for him. Should he have indulged in self-pity well might he have envied his dead comrades of Gaza.”

Other men were hidden away. Sergeant Martin O’Meara , a stretcher bearer, was awarded a VC for his bravery at Pozieres in 1916. For four days during heavy fighting he brought in wounded officers and men from no-man’s-land. Physically wounded and mentally shattered, he was “required to be kept in restraint” in the secluded Claremont Mental Hospital near Perth. O’Meara died alone from “chronic mania”, in 1935; he had spent 16 years in a straitjacket.

While the numbers of returned men who took their own lives may have peaked in the immediate post-war years, the losses continued throughout the 1920s and appear to have risen again in the 1930s with the challenges posed by the Depression years. It was the early ‘30’s which claimed the lives of two of Australia’s best loved heroes of the Great War: Captain Hugo Throssell VC and Major General “Pompey” Elliott.

CAPTAIN HUGO VIVIAN HOPE THROSSELL

CAPTAIN HUGO VIVIAN HOPE THROSSELL was born in Northam, Western Australia on 26 October, 1884, the youngest son of George Throssell, storekeeper and, later, premier. Throssell was a champion athlete and boxer, captained the local football team, and took up land in 1912 in the Western Australian wheatbelt with his brother, Ric.

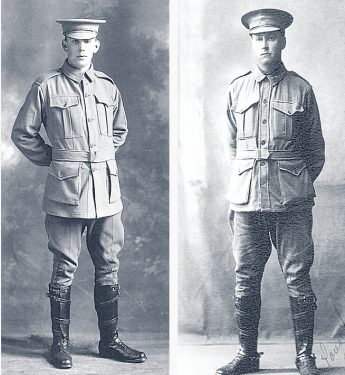

With the outbreak of war Hugo and Ric joined the 10th Light Horse Regiment, formed in October, 1914. Commissioned as a second lieutenant, Hugo arrived at Gallipoli on 4 August, 1915, three days before the charge at the Nek when nine officers and 73 men of his regiment were killed within minutes. Throssell was one of the leaders of the fourth and last line of attacking troops which was recalled after having advanced only a few yards. This experience increased his eagerness to prove himself in battle which came later that month at Hill 60.

For a week British and Anzac troops had sustained heavy losses as they attempted to dislodge the Turks from Hill 60, a low knoll almost a kilometre from the beach. At 1am on 29 August the 10th Light Horse was brought into action to take a long trench held by Turkish troops on the summit of Hill 60. As a guard, Throssell killed five Turks while his men constructed a barricade across their part of the trench. Throughout the night both sides threw more than 3000 bombs with the Western Australians picking up the bombs thrown at them by the Turks and hurling them back. Towards dawn the Turks made three rushes at the Australian trench, but were stopped by showers of bombs and heavy rifle fire. Throssell, who at one stage was in sole command, was wounded twice. His face covered in blood from bomb splinters in his forehead, he repeatedly yelled encouragement to his men. For his part in the battle Hugo Trossell was awarded the Victoria Cross, the citation reading:

“For most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty during operations on the Kaiakij Aghala (Hill 60) on the Gallipoli Peninsula on 29th and 30th August, 1915. Although severely wounded in several places during a counter-attack, he refused to leave his post or to obtain medical assistance till all danger was passed, when he had his wounds dressed and returned to the firing line until ordered out of action by the Medical Officer. By his personal courage and example he kept up the spirits of his party, and was largely instrumental in saving the situation at a critical period.”

Throssell was the first Western Australian to win the VC in the Great War, he was the only member of the Australian Light Horse to win the award, and was among the first Australians to receive the medal from the king at Buckingham Palace.

While recuperating from his wounds in London, Throssell was introduced to Katherine Susannah Pritchard who later became a famous Australian author (best known for her novels Coonardoo and Working Bullocks) and socialist. He eventually returned to active service, rejoining the 10th Light Horse in the Middle East where he fought in a number of engagements and achieved the rank of captain. Throssell was wounded in April, 1917 at the second battle of Gaza where his brother Ric was killed. He returned to the regiment for the final offensives in Palestine and led the 10th Light Horse guard of honour at the fall of Jerusalem. He returned home in 1918 and married Katherine in the next year.

In the following years Throssell was an outspoken opponent of war, and claimed that the suffering he had seen had made him a socialist. His stance on the futility of war outraged many people, especially as it was coming from a national war hero and the son of a respected and conservative former premier. His very public political opinions badly damaged his employment prospects, and he fell deeply into financial debt. Desperate, he devised a scheme which he thought would be a money-spinner. While Katherine was on a six month trip to the Soviet Union, he organised a rodeo on his Greenmount property on a Sunday, not realising that it was illegal to charge entry fees on the sabbath. The only money raised from the 2000 people who attended was a meagre silver collection for charity. The episode plunged Throssell further into debt and shattered his optimism.

Imagining that he could better provide for his wife and 11-year-old son if he left them a war pension, he shot himself on 19 November, 1933. He was 49.

Reference: “The Price of Valour” by John Hamilton, Pan, 2012.

MAJOR GENERAL HAROLD EDWARD “POMPEY” ELLIOTT

MAJOR GENERAL HAROLD EDWARD “POMPEY” ELLIOTT was born at West Charlton, Victoria, on 18 June, 1878. He was educated at Ballarat College, then the University of Melbourne where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Laws, sharing the final honours scholarship in law in 1906. He was called to the Victorian bar in 1906 and established a firm of solicitors. While the law may have been his profession, Elliott’s passion was soldiering. In 1900 he had interrupted his studies to enlist in the 4th Victorian (Imperial) Contingent, serving in South Africa where he obtained a commission, the Distinguished Conduct Medal, and was mentioned in despatches.

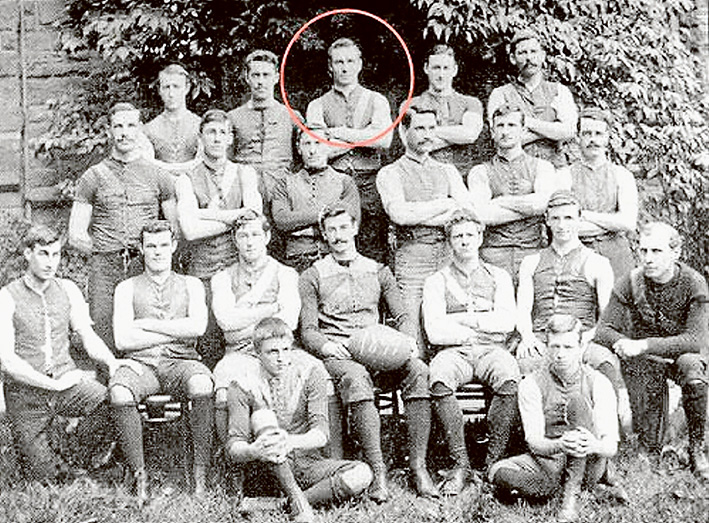

Elliott joined the militia on his return from South Africa and held the rank of lieutenant colonel in 1914. He was given the same rank in the Australian Imperial Force and command of the 7th Battalion. Elliott’s massive frame – he had been a good footballer and university champion shot putter-his energy, strength of character and explosive temper quickly established him as one of the characters of the force. His men called him Pompey after the footballer Fred “Pompey” Elliott, Carlton’s 1908 premiership captain. It was a nickname which did not please him but which clung to him to the end. Hard training and stern discipline were the foundation on which he built the 7th at Broadmeadows and then in Egypt.

Even before the Gallipoli landing Pompey was establishing his reputation within the AIF. It was the combination of his whole-heartedness, his absolute dedication to duty, coupled with his tempestuous personality, that generated a host of Pompey stories. And there was another ingredient too: his loyalty, his profound regard for and commitment to the officers and men he led, the kind of devotion manifested in the way he spent his time on leave visiting hospitals to see those of his men who had been wounded, and how he never stopped trying to think of ways his men could be better looked after in or out of the trenches. They soon came to realise that he had a genuine and profound regard for them despite his gruff volatile exterior.

Throughout the war Elliott was accompanied by his big black horse, Darkie. During inspections Darkie seemed to demonstrate an astounding ability to detect minor irregularities. He would draw Elliott’s attention to unshavenness or improper attire by stopping, throwing back his ears, and stretching out his neck. In fact it was Pompey, an accomplished horseman, who was directing the horse by subtly nudging Darkie’s neck. He would then pretend that Darkie had spotted the irregularity. Years after his men were still convinced that the horse had detected their errors for which the commander had berated them.

Elliott was shot in the foot on the landing at Gallipoli on 25 April, 1915, rejoined his battalion in June, and was in the midst of the fighting at Lone Pine in August where the Turks attacked repeatedly. Amidst savage fighting there were heavy casualties, with no fewer than four of Pompey’s men winning the VC at Lone Pine.

From Gallipoli the 7th Battalion returned to Egypt where it was sent 35 miles across the desert to defend the Suez Canal. The crossing was first attempted by the 14th Battalion which was forced to turn back. Elliott personally inspected the route, talked with officers familiar with it, and drew up a new timetable for the march, managing to get his men across with only a handful of casualties. On the march one man forgot the ban on smoking. Elliott characteristically started to scream at the man, even threatening to shoot him. Out of the ranks came a shout: “If you shoot him, I’ll shoot you.” When the soldier who called out was brought forward and explained that no one spoke to his brother like that, Elliott sent the man to his school for NCOs, with the rationale that anyone who could stand up to himself in full flight clearly had leadership potential.

On arriving at Suez, the water that the battalion had been promised was nowhere to be found. Elliott made one of the “vigorous protests” that he was becoming famous for, and was assured that the water would be available at 5.30 next morning. Elliott was up at 5am where he found that many of his men had been unable to sleep due to their thirst and were licking at the taps around the camp. He found the camp’s chief engineer who informed him that he had strict orders not to start the pumps before 8am as it would wake the corps commander. Elliott remounted his horse and tore off to corps headquarters where he informed a yawning staff officer that unless the water was turned on in the next five minutes, the 7th Battalion would be assembling and telling the corps commander what they thought of him. The staff officer made a phone call and Elliott was warned that he shouldn’t make such a fuss again. He simply replied that he would do whatever was needed to help his men when he had to.

Elliott was promoted to brigadier general early in 1916, assuming command of the 15th Brigade shortly before the disaster at Fromelles. Despite his inexperience in trench warfare, Elliott pointed out that the width of no-man’s-land was too great for the assault to succeed. Field Marshall Haig decided that the operation must go on, so Elliott did all that was possible to make it a success by himself going to the front line to personally inspect the lie of the land and encourage his men. He loathed the idea of throwing his men away uselessly and openly wept when it turned out that 1800 of the 5533 Australian casualties were from the 15th Brigade. These losses notwithstanding, the Brigade did magnificent work at the Battle of Polygon Wood at the end of September, 1917, with Elliott proving to be an inspiring leader. During the battle he went up to the front line to sort out the confusion there. Welsh Fusiliers were mixed up with the Australian troops. One wrote: “It was the only time during the whole of the war that I saw a brigadier with the first line of attacking troops.” Another said it was “… rare for anyone who combines authority and nous to be on the spot.” The Australians were unsurprised; their brigadier was just being himself. Later, Elliott wrote a report on the performance of a neighbouring British division: it was so critical that Lieutenant General Birdwood ordered all copies to be destroyed. Perhaps Elliott’s testiness could be partly explained by the fact that during this battle his brother, Captain George Elliott, a Military Cross winner, was killed. (George, a doctor, had been an excellent footballer, playing 80 VFL games prior to his enlistment. Although he did play with Fitzroy, most of his VFL games were with University which he captained in 1911 and 1912. He also represented Victoria.) Furthermore, a letter from home had revealed the collapse of Pompey’s legal firm, leaving him with a debt of 5000 pounds.

Elliott’s brigade also fought a second time at Villers-Bretonneux in April, 1918, the point at which the German offensive was halted. During this battle Elliott ordered that any British troops seen withdrawing were to be stopped and shot if they refused to turn back, angering their GOC Major General Heneker. Elliott quarrelled with everybody and was even known to put his battalion commanders and members of his staff under arrest when he lost his temper; such men resumed their duties when matters had blown over.

After the Battle of Amiens, Elliott’s brigade fought at Peronne at the end of August, 1918, and at the Hindenberg Line a month later. Early in October the Australians were withdrawn for a rest and did not take part in any further fighting.

After the armistice Elliott called a parade to hand out some last medals and gave the men a farewell speech to thank them for upholding his demanding standards. Later that afternoon the brigade returned to his headquarters, preceded by bands and colours. Each company circled the building and cheered for their commander. The senior colonel called for three cheers and told Pompey that the men wanted to show their appreciation for him; although it was a voluntary march ther were no absentees.

Elliott returned to Australia in June, 1919 and set about re-establishing his legal practice. In the general election held in that year he was top of the poll for the election of Victorian senators, and retained that position in the 1925 election. Although he did not make any special mark as a politician, Elliott was strident in his efforts to assist returned servicemen, particularly those with whom he had served. This would take the form of arguing in the Senate in relation to the new legislation being brought before it for the post-war defence forces, or personally assisting any members of his battalion. Elliott also played an important part in the 1923 Victorian police strike, making a call for members of the AIF to come to the town hall and sign up as special constables alongside General Sir John Monash. Many men, upon reaching the town hall, came specifically looking for Pompey, ready to stand behind him again.

In the immediate post-war years Elliott was in great demand as an unveiler as towns and organisations produced war memorials. Some had special significance: at Charlton, Ballarat and Ormond College. Of local significance was his journey to Mornington in October, 1921 to speak at the opening of an unusual memorial: a sizeable residence had been purchased, renovated and transformed into accommodation for homeless and destitute children. The property had been purchased by the family of Andrew Kerr, a 57th Battalion sergeant killed at Fromelles, as a lasting tribute to him. The building was of course “Glenbank”, built by the Reverend Caldwell in 1875, and narrowly saved from demolition in recent times. Elliott was frequently sought as a public speaker, particularly around Anzac Day. In 1922 he addressed crowds at Tongala and then Kyabram where he presented medals to returned soldiers (including one of his 7th Battalion originals) and then unveiled the Kyabram war memorial. In the days prior to Anzac Day he met with soldier settlers in Stanhope and Girgarre; the wisdom of settling returned soldiers with limited agricultural experience on farms was not universally accepted, and Elliott was keen to learn how these men were going.

In 1927 Elliott was promoted to the rank of major general, having still retained his involvement in the army. However, he felt that he was sidelined by the new leadership of the army; this was probably due to his outspokenness, particularly in relation to these appointments and the wartime records of some of those selected. Perhaps surprisingly for one who exuded so much confidence and bravado, Elliott was affected by what would now be called “post traumatic stress disorder”. The situation was exacerbated by the fact that he felt inadequate to help so many who turned to him for assistance with the onset of the Great Depression. Furthermore, his old grievance about being overlooked for promotion kept gnawing at him. So significant was his illness that, in the early hours of the morning of 23 March, 1931, at 52 years of age, Elliott took his own life while receiving treatment as an inpatient at a private hospital in Malvern. He had been admitted to the hospital late the previous afternoon after making an attempt to gas himself at his home in Camberwell. He left behind a wife (Kate) and two young children (Violet and Neil).

Elliott was buried on 25 March, 1931. After a short service at his home at 56 Prospect Hill Rd, his casket was drawn, with full military honours, including bands and escort party, on a gun carriage pulled by horses resplendent with black plumes, to the Burwood Cemetery, a march of some four miles. Newspaper reports tell of the thousands who either followed the cortege or lined the parade route. At the graveside there was a moving and significant service.

The cause of Elliott’s death was not disclosed at the time. A month later Smith’s Weekly divulged the confronting truth that Elliott had died by his own hand. Outraged returned soldiers gathered to burn down the newspaper’s offices and serious trouble was narrowly averted. The intense hostility towards Smith’s Weekly was confirmation of Elliott’s enduring esteem in the eyes of his men. It also underlined the jolting impact of his death; at a time of such pervasive misery and pessimism the sudden discovery that their idol, the leader that they admired above all others for his bravery and determination, had found it all too hard was a devastatingly bitter pill to swallow. Some refused to digest it at all, finding it simply unthinkable. While the reaction at the time was dismay, even disbelief, the manner of Elliott’s death has undoubtedly affected posterity’s perception of the man.

Reference: “Pompey Elliott” by Ross McMullin, Scribe Publications, 2002.

Footnote: Much of the information on Pompey Elliott has been gleaned from talks given, articles written, or the excellent biography referred to above. Ross McMullin really makes his subject come to life. He provides a host of Pompey stories and anecdotes which reflect both the character of the man and the typical digger humour of the times. Some that were not included in the feature article are part of Australian military folklore and are so entertaining that they have been reproduced alongside this special Anzac Day edition. Most of them are from Ross McMullin’s works.

The legend of Harold Edward ‘Pompey’ Elliott

ROSS McMullin’s biography Pompey Elliott is more than 700 pages and contains all of the stories and folklore surrounding this legend of the 1st AIF. The internet is also a profitable source of Pompey stories; invariably they are from papers or addresses given by Ross McMullin. The stories selected on this occasion have generally come from internet items.

EGYPT

Pompey’s hat: The best known Pompey anecdote, and what became the most often told story from the 1st AIF, was the story of Pompey’s hat. Pompey preferred what became known as the slouch hat to be worn by members of the 7th Battalion, being unimpressed with alternatives like caps or the British-style pith-helmet. During one parade in Egypt he made his preference known and, even though slouch hats were in short supply, he made the threat that any man from the 7th who was without a slouch hat at the next parade would find himself cleaning sanitary pans. After that parade Pompey went off to lunch at the officers’ mess, putting his hat under his chair as usual. When the meal ended he reached under the chair to retrieve the hat but was perturbed to find that it was no longer there. A series of searches undertaken at his instigation failed to locate the missing hat. Although many different views were expressed as to the fate of the hat, the most favoured version is that someone reached under the edge of the officers’ mess tent, grabbed the hat, and then either buried it in the desert or gave to a mate in another battalion. All Pompey could find by way of a replacement at short notice was one that was too small and had an odd pinkish colour. At the next parade there was considerable suppressed merriment in the ranks when Pompey struggled to retain his dignity while wearing this peculiar ill-fitting substitute.

The donkey: Although Pompey eventually came to see the funny side of the missing hat, the story that he most enjoyed recounting involved an incident which occurred when his battalion was marching near Cairo. The battalion happened to pass a group of hawkers and their tethered donkeys just as one of these animals, a male, was showing interest in a nearby female of the species. The male donkey’s interest was conspicuous and the passing soldiers reacted to this spectacle with ribald laughter. This annoyed the owner of the amorously inclined donkey; he darted over to it and gave one of its ears a savage twist whereupon the donkey’s desire deflated quickly. Shortly afterwards the battalion’s leading company, headed by its captain marching along in fine style with the senior sergeant just behind him, encountered a horse-drawn carriage containing two attractive women. One of them bowed and smiled to the captain, who gave an enthusiastic salute in return. Instantly a voice from the ranks was heard: “Twist his ear, sergeant.”

The newsboys: During the months in Egypt prior to the Gallipoli landing Pompey worked the troops particularly hard. He was nonetheless universally respected. Still, at times, they got their own back on their demanding CO. On one occasion they arranged for one of the local newspaper sellers to stand outside his tent in the early morning hours, declaring: Egyptian Times, very good news – death of Pompey the bastard.”

WESTERN FRONT

Wounded in the rear end: On one occasion Pompey was well forward talking to the commander of a tank when he received a wound to his left buttock. It was uncomfortably sore but not a serious wound, and he was contemptuous of suggestions that he should be evacuated to the rear for treatment. He did allow his own rear to be attended to as long as long as it did not interfere with his direction of the battle. The upshot was an unforgettable spectacle: the brigadier perched on a prominent mound, surveying the battlefield intently and dictating messages uninhibitedly, with his trousers round his ankles and underlings fussing over his behind. Onlookers were appreciatively amused by this further confirmation of his wholehearted commitment; there were also ribald remarks about the massive magnitude of his posterior. According to one of his colonels, “Seeing Pompey with his tailboard down having his wound dressed was one of the sights of the war.”

Making a splash: On one occasion Pompey felt that his battalion commanders were not pursuing the Germans across the Somme vigorously enough. With a contemptuous snort, Pompey decided to hazard his way – under fire – across a damaged bridge that was no certainty to support his hefty frame. Sure enough, he fell in with a spectacular splash. Signallers amused themselves spreading the message far and wide that “Pompey’s fallen in the Somme” with such gusto that the entire communication system for the 5th Division was blocked. Once again there was a memorable sequel: the arresting sight of Pompey, clad only in a shirt while his other clothes were drying, strutting about directing developments and dictating messages.

The ultimate deterrent: In late 1918 when Pompey found that some undisciplined soldiers were concentrating less on resisting the Germans than hopping into the grog left in the suddenly deserted estaminets and chateaux, he took characteristically assertive action. When a British officer was caught in the act, Pompey arranged for a notice to be issued declaring that the next officer caught looting would be summarily and publicly hanged and his body left swinging as a deterrent. He knew that this order was probably illegal, but desperate situations required desperate remedies. There was certainly no more trouble with looting. As Pompey, the solicitor in civilian life, drily observed afterwards, “No-one seemed inclined to make of themselves a test case under the circumstances.”